This may come as a shock to some. Bay Ridge has multiple monuments that venerate Confederate leaders. In today’s episode, we’ll take a look at the local monuments to Robert E Lee and Stonewall Jackson. We’ll find out how and why they got here, and how they have harmed our sense of history.

But this episode can’t stay hyper-local. It needs to look at a much broader historical context. That’s where our guest comes in, local Social Studies teacher John Hagan. John is one of many local activists who have spoken out against these monuments over the years. With his help, we will see our neighborhood through the lens of Reconstruction and Civil Rights era history. We will put these monuments in their true context.

These monuments are not just historical markers. They are racist and designed to intimidate people of color.

In this episode, we’ll learn about Robert E. Lee’s actual historical legacy in Bay Ridge. We’ll see how the United Daughters of the Confederacy twisted that history on a hyper-local scale. And we’ll explore our neighborhood’s history with brand-new research.

Audio Bookmarks

Quickly jump to key parts of the episode by clicking the links below…

- Introductions

- An Introduction to General Lee Avenue

- Acknowledgements and Qualifications

- Eleven Reasons To Remove Racist Monuments

- #1: They Were Traitors

- #2: Lee Was Never A U.S. General

- #3: They Were Inconsequential To Bay Ridge History

- #4: Their Veneration Is Part Of A Lost Cause Cult

- #5: Bay Ridge Was A Target Of Intentional Propaganda

- #6: The Monuments Are Used To Intimidate People

- #7: Their Veneration Obscures Real History

- #8: Taking Them Down Is A Necessary Part of Acknowledging Our Racist Past

- #9: The U.S. Has A Policy To Not Venerate Traitors

- #10: Tearing Down Monuments Is A New York Tradition

- #11: They Are Memorials To Our Inaction The Longer They Stay Up

- Further Listening and Reading

- How To Get In Touch

Show Notes

Today’s episode includes a lot of show notes. We’ve broken them down into sections based on how far into the podcast the references occur. You can jump around to relevant sections using the audio bookmarks above.

Introduction

2017 Protests Against Racist Civil War Monuments

At the start of the show, we talk about John’s experience and background. John has been present for two important protests in recent years. Both of them involved local residents demanding the removal of racist monuments.

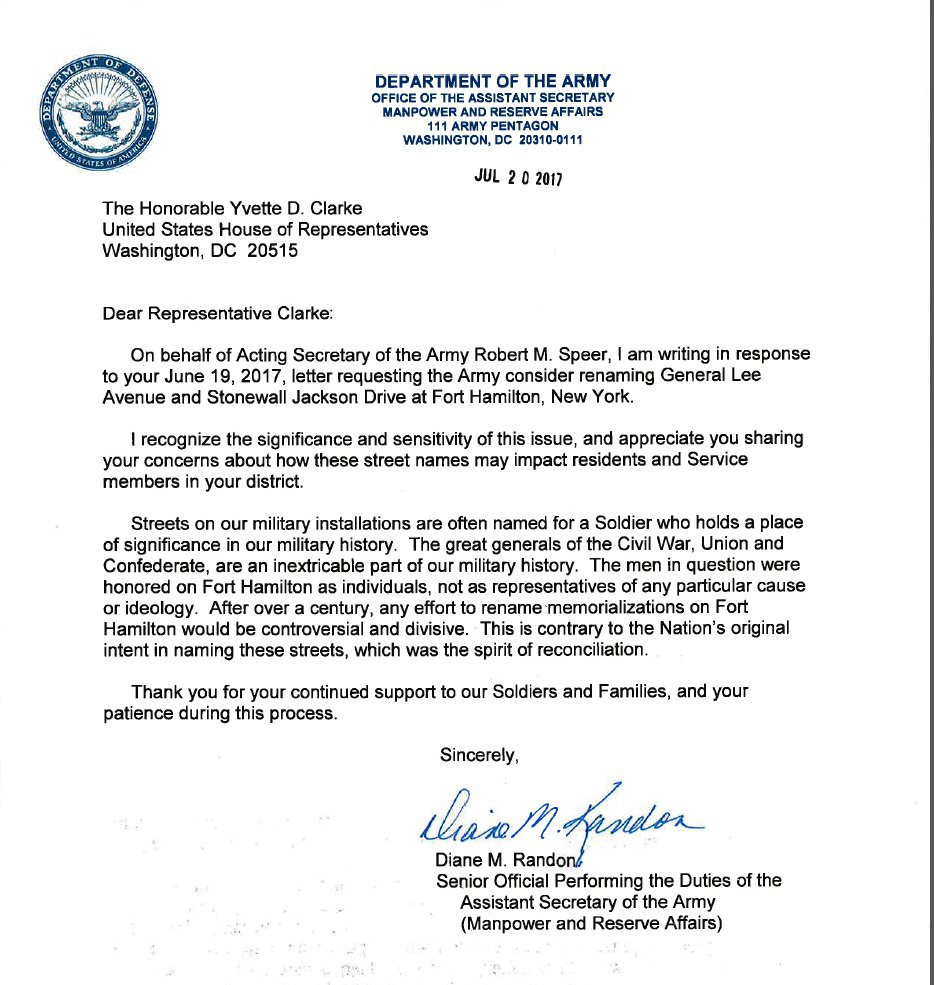

In 2017 a protest led by local activists called on Fort Hamilton to remove their confederate monuments. They demanded the renaming of General Lee Avenue and Stonewall Jackson Drive. The Army refused to budge, saying that they named the streets “in the spirit of reconciliation”.

The Army’s response implies that they named the streets after the Civil War. Later in the podcast, we reveal that the army likely named the streets between 1910-1950. There was nothing at that point to reconcile.

The 2017 protest did have one victory. It pushed the Episcopal Diocese of Long Island to remove of a monument on its property nearby. Much of the credit for this goes to Rev. Khader El-Yateem, who had good relations with the Diocese. A month after the first protest, workmen unceremoniously sawed off a plaque to Mr. Lee at St. John’s Episcopal Church.

We focus on the history of the church, and the tree, later in the episode.

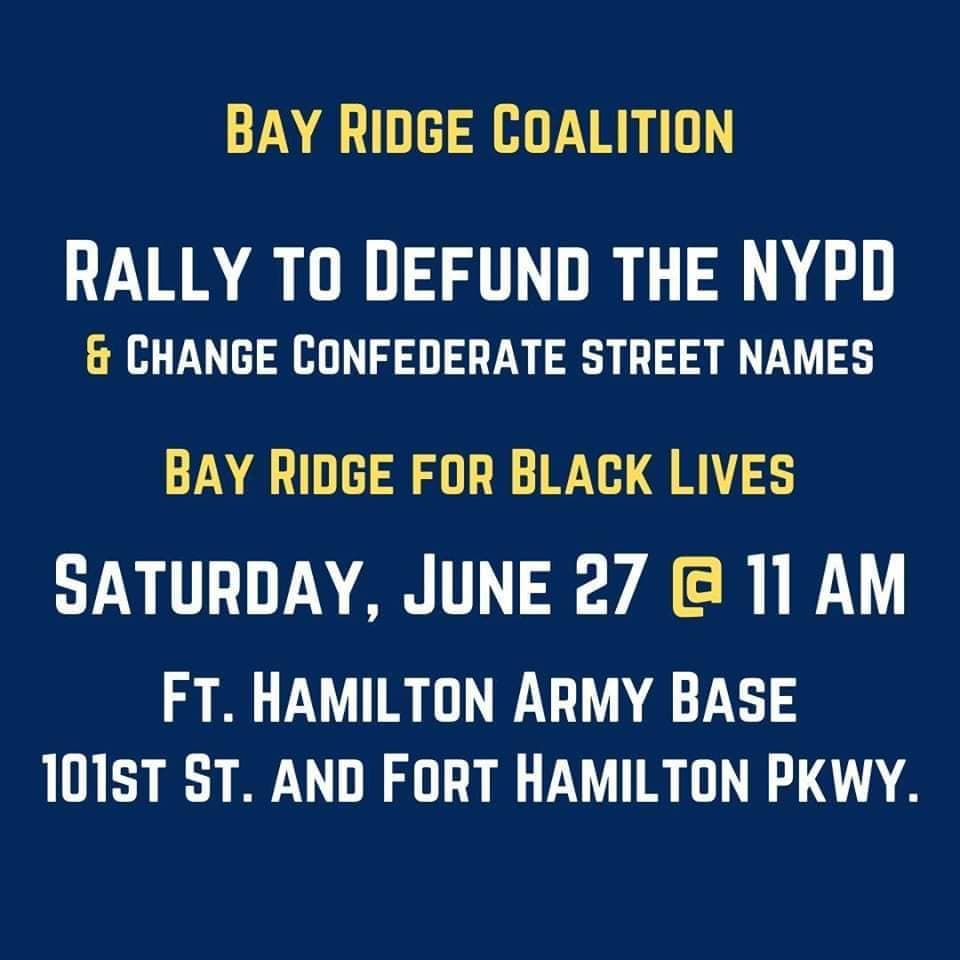

2020 George Floyd Protests

In 2020, the George Floyd protests ignited a renewed interest in renaming the streets. On June 27th, 2020, another protest occurred. Local activist groups organized under the name “Bay Ridge Coalition”. Among the groups participating were the Afrosocialist Caucus of the DSA, the local South Brooklyn DSA chapter, Bay Ridge For Social Justice, and Fight Back Bay Ridge, among others.

Days before the protests, political officials demanded the renaming of the streets. Politicians who were supportive of the movement in 2017, such as Yvette Clarke and Hakeem Jeffries, led the call. Max Rose joined in. Higher profile figures such as Mayor Bill DeBlasio and Governor Andrew Cuomo joined the bandwagon as well.

Reasons For Removing The Racist Memorials

Reason 1: They Were Traitors

Our first segment is straight-forward. As traitors to the United States, Jackson and Lee do not deserve a monument. We gloss over a lot of scholarship when we make this point, though. There’s a ton of great peer-reviewed material debunking the “Lost Cause” narrative. Some have gone so far as to call the “Lost Cause” a cult.

If you want to learn more info debunking the “Lost Cause”, there is good scholarship on the issue. Check out our “Further Reading” list at the bottom of the page for more. You can also check out the awesome Youtube series below…

Reason 2: Lee Was Never A U.S. General

I mean, enough said, right? Lee’s highest rank in the U.S. army was that of Colonel. To name a street “General Lee Avenue” is absurd. Giving him a Confederate rank shows how anti-historical these monuments are. The name furthers Lost Cause propaganda and skews history in a way that requires correction.

Reason 3: They Were Inconsequential To Bay Ridge History

We are going to be doing a bonus episode about Lee and Jackson’s time in Bay Ridge. There are a lot of details to explore. But as Dan promised, here’s some research material relating to Lee’s tenure at Fort Hamilton.

Lee Was Bored And Depressed In Bay Ridge

Lee took the job at Fort Hamilton to be closer with his wife at Arlington. However, multiple pregnancies and illnesses often kept her away. Thus, Lee ends up with a menagerie of pets to keep him company while he’s alone. Lee would invite friends up from Virginia to visit him for a few nights to break the monotony.

“My work now is all under cover & I expect to close my operations for the season early next month & to go on to Washinton for the winter, where I have been already notified my services will be wanting. I have had a very pleasant summer with some of our friends from the South constantly with us.” Letter from Robert E Lee to Henry Kayser, November 16th 1844. From Glimpses of the Past Vol 3, 1936.

“Diligent as Lee was, the routine soon became deadening. The old sense of frustration besieged him. He seemed to be weighted down by the very stones of the forts. During that first summer he left his station only twice – once to visit the Connecticut quarries from which he was getting stone and once to confer in Washington with Colonel Totten” Lee by Douglas Freeman

Lee’s Work in Bay Ridge Was Mostly Inconsequential

“The assignment, somewhat anticlimactic after his struggle with the Missisippi River, was little more than an exercise in his trained skills… though the work was routine, at least he could use his own initiative and make his own plans in redesigning the defensive network.” Lee: A Biography by Clifford Dowdey

Lee spent two or three of his five years undertaking repairs to Fort Hamilton. In addition to Fort Hamilton, he repaired Fort Lafayette (which Robert Moses demolished to make way for the Verrazzano Bridge). Lee also oversaw what would become Fort Wadsworth on Staten Island. At the time, Fort Wadsworth only consisted of two artillery batteries.

Much of Lee’s work was drudgery. He spent his time visiting nearby quarries for suitable stone. He shifted gun emplacements at forts that would never see actual combat. Lee had so much free time, his bosses tacked on extra work. This involved office work ordered by his superior in Washington D.C, Joseph Gilbert Totten. For example…

“The gray round of this uninteresting life was brightened somewhat in September by an appointment as a member of the board of engineers for the Atlantic coast defenses… Lee, as a junior officer, was made recording officer of the board.” Lee by Douglas Freeman

His boredom was extreme. The tedious office-work assignments took their toll. Lee begged for an assignment in the Mexican War, which his superiors finally granted… at the end of the war. He shipped off to Mexico from Governors Island and never looked back. His daughter Mary Anna Randolph Custis Lee would later write, upon Robert E Lee’s assignment to Mexico:

““The pleasant little cottage at the Narrows was dismantled promptly & all returned to Arlington…” from Biography of Robert E. Lee by Mary Anna Randolph Custis Lee

Lee was annoyed by the abolitionist movements in Brooklyn

We should note that the Mexican War was of great interest to slave-owning Southerners. If annexed, Southerners wanted Mexico diced up into new slave states. Lee was well aware of this while he lived in Bay Ridge. His racism didn’t start at the onset of Civil War.

For example, Lee’s disapproval of abolition can be found in a letter to his mother dated April 13th, 1844. The letter, sent from Fort Hamilton, describes his disgust with the politics of churches in Downtown Brooklyn. At the time, anti-slavery activism was very powerful in Downtown Brooklyn. Henry Ward Beecher and other famous abolitionists preached there.

The letter is currently in the George Bolling Lee Papers collection at the Virginia Museum of History and Culture.

There were other suggestions of his racism. Lee occasionally mentions not fitting in with the community. For example, when he first arrived he asked where he could find some household servants…

“I receive poor encouragement about Servants & every one seems to attend to their own matters. They seem to be surprized at my inquiring for help & have a wife too & appear to have some misgivings as to whether you possess all your faculties.” – Robert E. Lee to Mary Anna Randolph Custis Lee, April 19th 1841

Reason 4: Their Veneration Is Part Of A Lost Cause Cult

The Lost Cause myth has led to severe distortions of truth

John mentions a children’s book that depicted Stonewall Jackson as kind to his slaves. The book is called Stonewall Jackson’s Black Sunday School, published in 2010.

The book depicts Mr. Jackson’s attempts to educate black slaves as generous. In truth, Jackson’s school is example of racist attitudes at the time. Many whites felt that blacks required white-dominated instruction and discipline in order to become capable of self-control. This process of instruction was expected to last generations. Jackson felt slavery was appropriate condition for blacks until such “betterment” was achieved.

The Civil War was about slavery, not states rights

John mentions multiple times in the show one of the best refutations of the Lost Cause mythology he has seen. It comes from former Brigadier General Ty Seidule, a history professor at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point.

His viral takedown of the Lost Cause comes from the problematic right-wing fake university PragerU. We promise this will be the only time on this show that we share something from PragerU… but the content itself is solid.

Reason 5: Bay Ridge Was A Target Of Intentional Propaganda

During the episode, we explain that the United Daughters of the Confederacy targeted Bay Ridge for propaganda. This was most likely instigated by a church pastor in the 1900s trying to drum up donations. As a result, Lee and Jackson got far more attention than they deserve.

A Church In Debt

We outline that St. John’s Episcopal Church had undergone a renovation at the turn of the century. This is described in an article from the Baltimore Sun on January 7th, 1898, from their “Topics In New York” section…

“The new edifice of St. John’s Protestant Episcopal Church, at Fort Hamilton, was consecrated by Bishop Littlejohn today… Originally it was established as a military chapel. Gen. “Stonewall” Jackson was baptized in this church by Rev. Mr. Choefield, April 29, 1849.” – Baltimore Sun, January 7th 1898

In the ensuing decade, the church was struggling to become self-sufficient, according to Diocese records. It was the only church on Long Island suffering in this way…

“St. John’s Church, Fort Hamilton, the Rev. Wm. A. Swan, Rector, is now the only organized parish being aided by the Archdeaconries. The grant to this parish is being reduced year by year so that in a few years, without unnecessary hardships, it will become self-supporting. A careful examination of the records of this parish convinces me that in spite of many obstacles this work is stronger and more promising than it has been for years.” – Journal of the Forty-Fourth Convention of the Diocese of Long Island, 1910

Hitting up the United Daughters of the Confederacy for money

The Diocese was hopeful that the church would eventually become self-sustaining. That is in no small part due to Rev. Swan’s outreach to the United Daughters of the Confederacy. According to their New York chapter as early as 1903, a mere five years after the church renovations…

”We also assisted the little parish church at Fort Hamilton, which appealed to us, and the letter, to touch our hearts I suppose, stated that General Lee and General Jackson had been communicants there.” – Minutes of the Annual Convention of the 1903, United Daughters of the Confederacy, p127

A decade later, the United Daughters of the Confederacy were much more verbose about their attention toward Bay Ridge. While in 1903 their report seemed a bit wary of Rev. Swan, by 1912 that wariness was gone. They were donating large sums of money, and their reports were dripping with florid praise…

”Passing along the beautiful section of land which borders on our harbor, known as Bay Ridge, and following the road until Fort Hamilton is reached, one comes to a quaint picturesque building just opposite the Parade Ground. It is the Episcopal Church of St. John, loved and revered by Southerners because within its walls Stonewall Jackson was baptized, and Robert E. Lee worshipped and communed many years ago, while both were young men in the United States service. By the side of the church a tree of Norway maple was planted by General Lee while he was stationed at the Fort. Our Historian, Mrs. J.D. Beale, called my attention to the condition of the tree and expressed the opinion that it would be a beautiful work for us to restore and mark it. At our next meeting the Chapter warmly endorsed this idea, and shortly after we made a trip to the spot one day last March. We found the tree in very bad condition, one large branch had been broken off, and, bare and leafless, it seemed to appeal to us mutely, to come to its aid. Examined by the Park Commissioner of Brooklyn it was pronounced in a condition to command immediate attention if we wished to save it; a hole twelve feet deep extended along the center, and made it an easy prey for the first storm which might shake its aged branches. You may well imagine that we lost no time in bidding the work of restoration begin. The Park Commissioner was appealed to, to restore it as an historical tree, which he engaged to do, free of charge to us, and we were then to undertake the marking of it. They invited us to come down and see the work of restoration, which we did, to our interest and edification. The tree was treated very much as a decayed tooth is, being cut out, cleaned, disinfected, filled, and then (the resemblance ceasing) the cavity covering with a coating of tar. Iron girders were also used to hold the branches firmly in place. We then ordered a handsome substantial bronze tabled securely fastened upon the trunk and bearing this inscription-

This tree was planted by

General Robert E. Lee

While stationed at Ft. Hamilton

in 1842-1847

The tree has been restored and this tabled placed upon it

By the N. Y. Chapter

United Daughters of the Confederacy

April, 1912

Early in October I went down to see the work completed, and ladies, as I stood there in the autumn sunshine and looked at that tree, its branches still green with leaves, renovated and restored and marked for all time, I felt a throb of pride and gratitude that we had indeed done a good work, and one of which every United Daughter of the Confederacy would approve.” – Minutes of the Annual Convention of the 1912, United Daughters of the Confederacy, p 372

Mutually beneficial propaganda

By 1913, the United Daughters of the Confederacy were making annual trips to Bay Ridge. They continued to pour money into the church. Members thanked people for sneaking food to Confederate prisoners at Fort Lafayette during the war. The club spent money on new stained glass windows for the church. Even the national president of the United Daughters of the Confederacy visited the neighborhood.

By 1921, they put up a new plaque for the tree after the old tree died. In 1922, they added a plaque inside the church itself. Rev. Swan continued to bask in the donations…

“The service, which was conducted by the Rector, the Reverend Mr. Swan, drew to that secluded spot five hundred devoted men and women of the South. The capacity of the church was exhausted long before the hour appointed, but those who journeyed thither waited reverently without, catching what glimpses they could of the service through the windows and doors and joining in the music, especially General Lee’s favorite hymn, “How Firm a Foundation, Ye Saints of the Lord.” – Minutes of the Twenty-Ninth Annual Convention, 1922, United Daughters of the Confederacy, p226

This continued with the addition of more plaques and monuments. This includes one inside the church itself. The donations would continue until well into the 1950s, when the UDC dropped a literal boulder outside Lee’s former on-base residence.

The Naming of the Streets

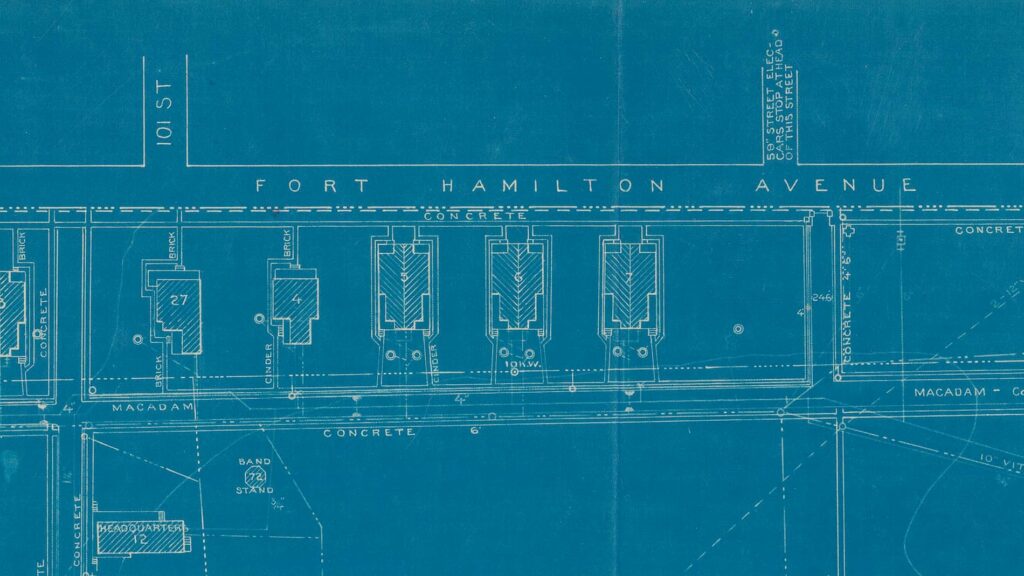

While there are no solid dates for when the Army named the streets, there are a few interesting hints. Dan mentions detailed blueprints for the base, dating from 1913. The plans do not name any of the on-base streets. However, the Army clearly marked public roads. The plans have so much detail they mention ditches and sewage systems. Again, no street names are present.

It’s unlikely the Army needed street names at this point. The Army identified buildings by number, purpose, or battery number. Why have street names when addresses were pointless? All mail went to a single on-base post office.

This means that the naming of the streets most likely occurred some time between 1913 and the 1950s. The most likely time frame is between the onset of World War Two and the construction of the Verrazzano Bridge.

During World War Two, the Army dramatically expanded the base. WPA crews built new roads, according to a New York Times article from July 19th, 1941. Perhaps the base added street names when it built new residential housing in the 1950s to help families find their way around. Or perhaps the Army renamed the streets when Robert Moses built the Verrazzano Narrows. The bridge cut through part of the old base and required the Army to reconfigure the road layout.

The Spirit of Reconciliation

These new facts fly in the face of the U.S. Army’s official reason for not wanting to rename the base. As Dan mentioned in the podcast, the Army claimed that they named the streets in the “spirit of reconciliation”. The Army made this claim in a response to Congressperson Yvette Clarke’s request to rename the streets in July of 2017.

Reason 6: The Monuments Are Used To Intimidate People

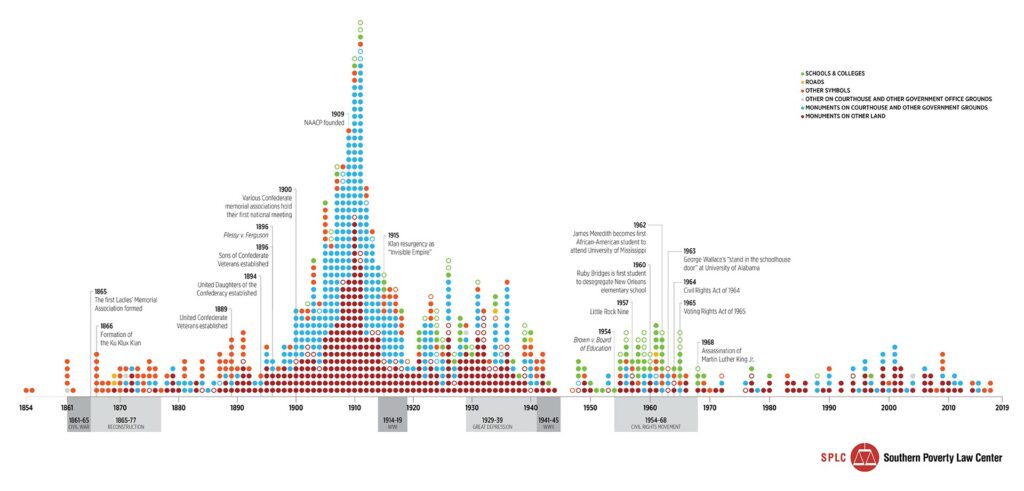

John cites an excellent map from the Southern Poverty Law Center. It shows when most confederate monuments went up in the United States.

Note that the graph above does not include the Fort Hamilton streets. According to the SPL both street names have an unknown installation date, and thus aren’t part of the dataset.

Bay Ridge’s Confederate monuments mostly go up near the tail-end of the big spike around 1900. Other monuments would go up until the 1950s.

Reason 7: Their Veneration Obscures Real History

Abner Doubleday, Commander of Fort Hamilton

We mention that Lee and Jackson often obscure other interesting historical figures in Bay Ridge. A good example is Abner Doubleday, whose actions on the first day of the Battle of Gettysburg were essential to winning the battle against Robert E. Lee.

Mr. Doubleday was the man in command of Fort Hamilton in 1861, when the Civil War broke out. He left Fort Hamilton much like Robert E. Lee did, to join a war. Lee left Fort Hamilton to seek action in the Mexican War, which Lee hoped would expand the number of slave states by annexing Mexico. Doubleday, on the other hand, left Fort Hamilton to fight for the eradication of slavery.

General Lee Avenue is 3,000 feet long and the main thoroughfare for the Fort Hamilton Army Base. Doubleday Lane is 400 feet long and connects to a few residential buildings, including a small dead-end roundabout named Doubleday Circle.

The NAACP and Thurgood Marshall vs. Fort Hamilton

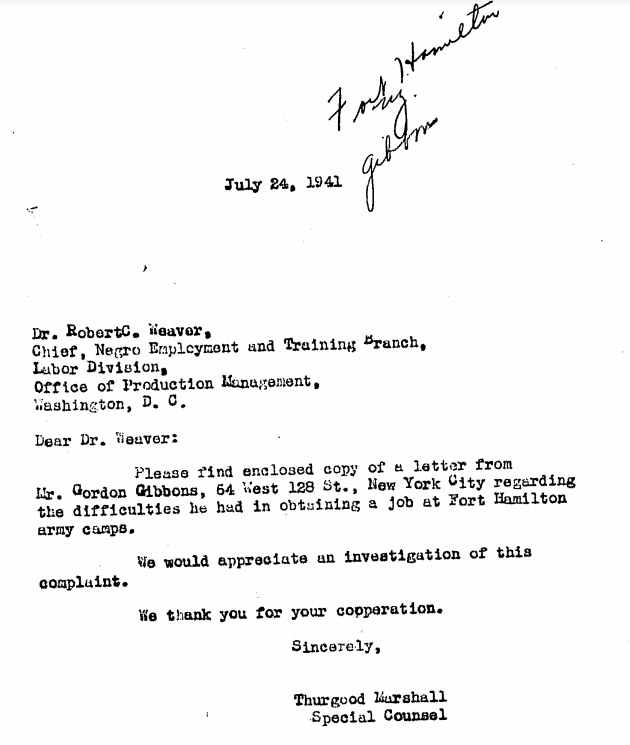

In 1941, a black union carptenter named Gordon Gibbons lodged a complaint against Fort Hamilton. In his complaint, Gibbons said that the Army denied him and other black union workers jobs. Each morning, Army officers would only pick white workers to assist in road construction on the base. One of these roads may very well have been General Lee Avenue.

His complaint fell on deaf ears at the A.F.L., and he requested the aid of the New York City chapter of the NAACP. The complaint passed the desk of Thurgood Marshall, future justice of the Supreme Court.

You can see a snippit of Mr. Gibbons story in the Papers of the NAACP, Part 13: NAACP and Labor, Series A: Subject Files on Labor Conditions and Employment Discrimination, 1940-1955, in Folder 001432-017-0601.

Abuse of Black WACs on the base in the 1950s

The workplace discrimination didn’t seem to stop. In 1954, a black Womens Auxiliary Corps (WAC) member told the New York Amsterdam News that the Army was assigning her demeaning tasks. White WACs were not subject to this treatment. She had felt her race played a role in her assignments and deployments. Instead of addressing the issue, her superiors gave her mental health tests and described her as having a “chip on her shoulder”. They denied everything when confronted by the press.

The case is described in detail in a March 20th, 1954 article in the New York Amsterdam News titled “Is Fort Hamilton Biased? Army Says No.”

Reason 8: Taking Them Down Is A Necessary Part of Acknowledging Our Racist Past

In this part of the podcast, we pick apart how renaming these streets is essential to fully coming to terms with our racist past. John discusses the power of New Orleans’s mayor Mitch Landrieu’s speech as a particularly powerful call to action for the removal of racist monuments.

Reason 9: The U.S. Has A Policy To Not Venerate Traitors

Dan discusses in detail how Benedict Arnold has been treated and venerated in monuments, plaques, and sculptures. You can see some of the examples below.

Reason 10: Tearing Down Monuments Is A New York Tradition

Dan quickly references the tearing down of the Statue of King George in the episode. The event occurred shortly after the ratification of the Declaration of Independence. An equestrian statue of the king was torn down by protestors in Downtown Manhattan. It was melted down to make musket balls i.e. bullets.

Some Royalists probably complained that you can’t erase history.

Reason 11: They Are Memorials To Our Inaction The Longer They Stay Up

Our final point needs little elaboration. Yes, these monuments venerate Robert E Lee and Stonewall Jackson. But they also venerate the fact that we, as a neighborhood, have tolerated them for so long. That must change.

Additional Reading

- The full Statement by the American Historical Association on Confederate Monuments. John quotes a small part of it at the end of the episode.

- “Whose Heritage? Public Symbols of the Confederacy” by the Southern Poverty Law Center

- “The Wars of Reconstruction: The brief, violent history of America’s most progressive era” by Douglas R Egerton

- “Stony The Road: Reconstruction, White Supremacy, and the Rise of Jim Crow” by Henry Louis Gates Jr.

- “Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877” by Eric Foner

- “Race and Reunion” by David W Blight

- “How the South won the Civil War” by Heather Cox Richardson